JULY 2, 1863:

The

Battle of Gettysburg (Day Two):

The first day at Gettysburg ended with an

apparently complete Confederate victory. The Union had been chased out of

Gettysburg proper, the road network was in Confederate hands, and nothing could

seemingly stop General Lee from marching on Harrisburg, at least. Lee was

concerned, however, about the large, supposedly shattered Union force that

would be in his rear, and decided to dedicate the Second of July to thoroughly

impairing the ability of the Army of the Potomac to challenge him. The

essential destruction of the most crucial of Union armies would force the

United States to recognize the independence of the Confederacy.

General George Meade, the General-in-Chief of the Army of

the Potomac arrived at Gettysburg after dark on the first day, and after

conferring with his subordinates decided that it was an ideal place to do

battle with Lee's army. Despite losing most of two Corps on the first day,

Meade was confident, as he anticipated reinforcements totaling up to 100,000

men to arrive and strengthen his defensive position. And, indeed, overnight, four of the remaining five

Corps of the Army of the Potomac began arriving and emplacing, By dawn, Meade’s

forces were more than twice greater than his entire force on the first day, and

they were holding the high ground.

Robert E. Lee had several choices to consider for his next

move. His order of the previous evening that Ewell occupy Culp's Hill or

Cemetery Hill "if practicable" was now impossible, because the Union

army was now in strong defensive positions with compact interior lines. His

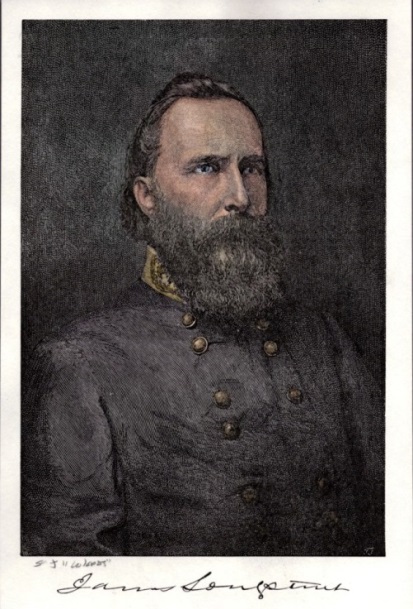

senior subordinate, General James Longstreet, saw the Union position as nearly

impregnable and counseled a strategic move, advising Lee that the Army of

Northern Virginia should leave its current position, swing around the Union

left flank, and interpose itself on Meade's lines of communication, inviting an

attack by Meade that could be received on advantageous ground. Longstreet

argued that this was the entire point of the Gettysburg campaign, to move

strategically into enemy territory but fight only defensive battles there.

Lee rejected this argument because he was concerned about the

morale of his soldiers having to give up the ground for which they fought so

hard the day before. He wanted to retain the initiative and had a high degree

of confidence in the ability of his army to succeed in any endeavor, an opinion

bolstered by their spectacular victories the previous day and at

Chancellorsville. He was therefore determined to attack on July 2nd. As of the

early morning the Union forces had resolved themselves into an inverted “U” –shape

occupying Cemetery Ridge, Culp’s Hill and Cemetery Hill south of town. Lee

contemplated attacks on the twin arms of the U, and a charging attack into the

open end of the “U.” Attacked on both sides, Lee figured, the Union forces

would be overwhelmed. Lee’s error was that the “U” he envisioned was really

more in the shape of a walking cane, shortened on one side, and that there were

Yankee troops on Power’s Hill in the mouth of the “U”.

Had J.E.B. Stuart’s cavalry been nearby, it is possible that

Lee might have had a better picture of the ground assault positions. But Lee

was essentially blind to Union movements, and was suffering from a strange,

uncharacteristic, obstinacy about the course of the battle. Lee had begun to

believe in the invincibility of his Army of Northern Virginia, and worse yet,

in his own infallibility. After a string of victories, Lee had begun to believe

that the Union Army of the Potomac was intimidated and poorly-led. He was wrong

on all counts: His army was not invincible and he was not infallible. And the

Army of the Potomac hadn’t been intimidated since First Manassas, it had merely

had equivocal leadership. This was no longer the case. Lee was right about

George Meade---he was a cautious man and unfamiliar with his command---but he

was not Ambrose Burnside, Joe Hooker or George McClellan. He was willing to

fight under good conditions, and the conditions at Gettysburg were a gift to

Meade.

Lee’s plan was also spoiled by the necessity of James

Longstreet having to countermarch his troops in the vicinity of the Emmitsburg

Road in order to keep them hidden from Union observers on Little Round Top.

Thus, his assault, scheduled for 10:00 AM, was not launched until 4:00 PM. Longstreet

was also bedeviled by Union General Dan Sickles, who had inexplicably moved his

Division out of line and into the area of Devil’s Den and The Wheatfield. This

had several effects: First, Sickles’ force was isolated and subject to being

overrun; second, Meade had to stretch his lines thin to accommodate the gap that

Sickles’ departure had created, giving the Confederates a natural weak spot to

exploit; third, Sickles had moved his troops right into Longstreet’s intended

path, fouling up the plan to enter the mouth of the “U” uncontested; and

fourth, though Sickles had acted precipitately, he had wisely anchored his men

in the roughest patch of Gettysburg real estate, ever after known as “Devil’s

Den.”

Sickles has been blamed for the Union nearly being defeated

at Gettysburg, and Longstreet has been blamed for the Confederacy’s defeat, but

both men’s actions made some sense, though Sickles is harder to defend. Sickles

had been blamed for prematurely surrendering the Hazel Grove at

Chancellorsville, a move that led to the Union’s defeat, and so he chose to be

more aggressive at Gettysburg. Sickles violated orders and complicated it all

with bad tactics, inept though understandable in a “political general.”

On the other hand, Longstreet, a skilled veteran commander

realized that had he not taken steps to shield his men from view they would

have been cut down on the march. Lee simply did not know the ground at

Gettysburg. Lee’s plan, as conceived, could not have worked.

The Second Day at Gettysburg resolved itself into several

localized and interlinked battles:

1. The Battle of

Cemetery Hill:

This battle had been

contemplated by Lee as a “demonstration,” a feint or a distraction from

Longstreet’s assault against the open mouth of the “U”. As it turned out, it

became an assault against the center of the Union line, the bow of the “U”.

General R.S. Ewell C.S.A. began his “demonstration” upon hearing the sound of

Longstreet's guns to the southwest. For three hours, Ewell limited his attack

to an artillery barrage from Benner's Hill. Although the Union defenders on

Cemetery Hill received some damage from this fire, they returned counterbattery

fire with a vengeance. Cemetery Hill is over 50 feet taller than Benner's Hill,

and the geometry of artillery science meant that the Union gunners had a

decided advantage. Ewell's four batteries were forced to withdraw with heavy

losses.

2. The Battle of

Cemetery Ridge:

The Battle of

Cemetery Ridge was the last battle of the Second Day, and it could very well

have been decisive to the Confederate cause had things gone just a bit

differently. At 6:00 PM, Confederate

forces from Seminary Ridge managed to go over the crest of parallel Cemetery

Ridge against almost no Union opposition. For a time, the only Union soldiers in this

part of the line (“The Copse of Trees”) were General Meade and some of his

staff officers, as so many Union troops had by then been dispatched to Devil’s

Den, The Wheatfield, and The Peach Orchard.

Having marched down one hill, across a valley, and up

another in the relentless 100-degree heat of the day, the Confederates were

forced to a halt to regroup, and this gave the Union adequate time to

counterattack. General Winfield Scott Hancock ordered the men of the 1st

Minnesota, Harrow's Brigade, of the 2nd Division of the Second Corps to

"Advance, and take those colors!" The 262 Minnesotans charged an

Alabama brigade with bayonets fixed, and they blunted their advance but at a

horrible cost—215 casualties (82%), including 40 deaths or mortal wounds, one

of the largest regimental single-action losses of the war.

Despite superior Confederate numbers on the Ridge, the small

1st Minnesota had checked the Rebel advance, and the Alabamians were forced to

withdraw. The retreating Confederate commander, Brigadier General

Ambrose R. Wright, later that evening told Robert E. Lee that it was relatively

easy to get to the crest, “but it was difficult to stay there,” and it is

probable that Lee derived some false confidence from Wright about the ability

of his men to reach Cemetery Ridge, hence encouraging Lee to order Pickett’s

Charge the next day. By then, any Union weakness in the center had been

rectified. On the Third Day, Lee’s men were marching into a deathtrap.

3. The Battle of

Culp’s Hill:

The loss of Culp’s Hill,

near the bow of the “U” or what eventually became a “fishhook,” would have been

catastrophic to the Union army. Culp’s Hill dominated Cemetery Hill and the

Baltimore Pike, the latter being the Union army’s main supply route and the

road to the capital. Holding it meant blocking any Confederate advance on

Baltimore or Washington, D.C. Compared to Cemetery Hill and other areas of the

field, Culp’s Hill was thinly defended at the outset, though the troops were very

well dug in. Around 7:00 PM, Ewell chose

to begin his main infantry assault here. He sent three brigades up the eastern

slope of Culp's Hill against a line of breastworks manned by the Twelfth Corps,

which held off the Confederate attack for hours. Large numbers of Union

reinforcements were sent to Culp’s Hill to beat back the assault. The

Confederates were shocked at the strength of the Union breastworks on the crest

of the hill. Their charges were beaten off with relative ease by the 60th New

York, which suffered very few casualties. Confederate casualties were very

high. One of the New York officers wrote "without breastworks our line

would have been swept away in an instant by the hailstorm of bullets and the

flood of men," although the attackers established a foothold in some

abandoned Union rifle pits near Spangler’s Spring. In a rare Civil War night action, the battle

continued after dark, and random shooting went on all night. In the darkness, several Rebel units attacked

each other. The Battle of Culp’s Hill continued into the third day.

4. The Battle of

Little Round Top:

At the southern

end of the battlefield, Longstreet’s offensive began around 4:00 P.M. Major Gen. John Bell Hood's division was

assigned to attack up the eastern side of the Emmitsburg Road, but parts of

Hood's division detoured over Big Round Top and approached the southern slope

of Little Round Top in order to avoid Sickles’ entrenched troops, the storied 2nd

U.S. Sharpshooters, the rough terrain near Devil’s Den, and, also, because of

command confusion.

At this point in

time, Little Round Top was undefended by the Union; it was supposed to have

been in Sickles’ area, but Sickles was in Devil’s Den. When Meade discovered

this situation, he was enraged and hurriedly dispatched messengers to direct

reserves to the hill. Hearing of Meade’s need, Colonel Strong Vincent,

commander of the third brigade sent his four regiments to Little Round Top. The

16th Michigan, the 44th New York, the 83rd Pennsylvania, and, at the extreme

end of the line, the 20th Maine were ordered to hold their positions at all

costs. They arrived just ten minutes before Hood’s men.

The approaching Confederates were the 4th, 15th, and 47th

Alabama, and the 4th and 5th Texas. Ordered to take the hill, the men were

already exhausted, having marched more than 20 miles that day. The day was hot

and their canteens were empty.

Approaching the Union line on the crest of the hill, the

Confederates were thrown back by the first Union volley and withdrew briefly to

regroup. The 15th Alabama attacked the Union left flank consisting of the 358

men of the 20th Maine.

To hold the line, Colonel Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain first

stretched his troops to the point where his men were in a single-file line,

then ordered the southernmost half of his line to swing back or "re-fuse

the line," forming an angle to the main line in an attempt to prevent the

Confederates from flanking them. Despite heavy losses, the 20th Maine held

through two subsequent charges for a total of ninety minutes.

At the last, knowing that his men were out of ammunition,

that his numbers were being depleted, and that another charge could not be

repulsed, Chamberlain ordered a maneuver that was considered unusual for the

day: He ordered his left flank, which had been pulled back, to advance with

bayonets in a "right-wheel forward" maneuver. As soon as they were in

line with the rest of the regiment, the remainder of the regiment charged, akin

to a door swinging shut. This simultaneous frontal assault and flanking

maneuver halted and captured a good portion of the 15th Alabama. At the same

time, the 20th Maine’s Company B who had been placed by Chamberlain

behind a stone wall 150 yards to the east, having been out of range of the

battle until now, finally opened up on the Confederates with enfilading fire.

Attacked on three sides, the Confederates broke. Chamberlain’s men took more

prisoners than there were surviving members of the 20th Maine.

While the 20th Maine’s actions are justly famous

and while Chamberlain deserved his eventual Medal of Honor, the other Union

regiments on Little Round Top did yeoman service this day. The 4th and 5th

Texas attacked the 16th Michigan, on the Union right. Before the Michiganders

could be demoralized, reinforcements arrived in the form of the 140th New York

and a battery of four guns---Battery D, of the 5th U.S. Artillery. Simply maneuvering

these guns by hand up the steep and rocky slope of the hill was an amazing

achievement. However, this effort had little effect on the action since the

artillerymen were exposed to constant sniper fire and could not work

effectively. More significantly, however, they could not depress their barrels

sufficiently to defend against incoming infantry attacks. The 140th New York charged

into the fray of the battle, driving the Texans back and securing victory for

the Union forces on the hill. Union forces held the hill throughout the rest of

the battle, enduring persistent fire from Confederate sharpshooters stationed

around Devil's Den.

Little Round Top remained the site of constant skirmishing

and was the starting point for a Union counterattack at dusk, launched in the

direction of The Wheatfield.

5. The Battle of

Devil’s Den:

Devil’s Den is a

boulder-strewn ridge near Little Round Top. Inaccessible

by direct assault, Longstreet’s Confederates (under John Bell Hood) entered

Devil’s Den through Rose Woods at about 4:00 PM, and hit Sickles’ Union line

head-on. For over an hour both sides participated in a standup fight of unusual

ferocity.

The pressure grew great enough that the Union called for

reinforcements. Nonetheless, the Confederate assault was inexorable, as wave

after wave of fresh troops poured into the rocky defiles of Devil’s Den. As one of the Union commanders later related,

the Confederates "converged on me

like an avalanche, but we piled all the dead and wounded men in our

front."

The Union ground defense was fierce. The Confederates were

also receiving murderous fire from the crest of Little Round Top, but they kept

pushing forward. The rocky, broken ground that the survivors fought over would be

remembered as the "Slaughter Pen," and the small creek of Plum Run

became known as "Bloody Run"; the little river valley of Plum Run

earned the moniker "The Valley of Death." The pressure on the Union

brigades was eventually too great, and the Blue was forced to call for a

retreat. Hood's division secured Devil's Den. The battered Confederates spent the

next 22 hours in Devil's Den, firing across the Valley of Death at Union troops

massed on Little Round Top. The assaults

by Hood's brigades were classic, tough infantry fights. Of 2,423 Union troops

engaged, there were 821 casualties (138 killed, 548 wounded, 135 missing); of the

5,525 Confederates engaged they lost 1,814 (329 killed, 1,107 wounded, 378

missing).

6. The Battle of

The Wheatfield:

The Wheatfield is,

literally, a wheat field. Owned by the Rose family in 1863, The Wheatfield

battlefield also consists of Rose Woods and Stoney Top, both of which are

adjacent to Devil’s Den. Rose Woods had acted as the Confederate approach route

to Devil’s Den, and as Hood’s men took Devil’s Den around 5:15 PM, the fighting

spilled out of Devil’s Den and into The Wheatfield. The combatants were no less

aggressive in The Wheatfield than in Devil’s Den, and The Wheatfield soon

became known as “The Bloody Wheatfield.” Eleven brigades battled in the area

until 7:30 PM.

Early in the battle, the Confederates seized Stoney Top,

using it to fire on Union men in The Wheatfield. Reinforcements retook Stoney

Top, and then The Wheatfield, but Confederates freed up from the fighting in

the Peach Orchard retook The Wheatfield in vicious hand-to-hand combat. U.S.

Regulars (not State Militia) arrived, and The Wheatfield changed hands once

again, until more Confederates arrived, turning the battle once again. The

Regulars retreated in good order. Encouraged, the Confederates charged out of

The Wheatfield, but were met by withering fire from the Pennsylvania Reserve

Division (including men from Gettysburg) who cut them down. Reeling pell-mell

back across The Wheatfield, the Rebels surrendered the ground permanently.

Though The Wheatfield remained quiet afterward, it was a

charnel house of the dead, and a hell for the wounded and dying men who lay

there forgotten. Of the 21,000 men who fought in The Wheatfield, 7,000 were

casualties. Suffering in the 100-degree heat, many dehydrated wounded tried to

crawl to Plum Run for water, but died in the attempt or fell in and drowned.

Their blood stained the little creek red.

7. The Battle of

The Peach Orchard:

At around 5:30,

Confederates streamed into The Peach Orchard, then also a Rose property which

lies directly northwest of The Wheatfield. The Peach Orchard was the site of

General Sickles’ Command Post, and was heavily defended. Union artillery, solid

shot and canister, literally tore men apart in the arbor. Despite this,

increasing Confederate pressure led to the abandonment of The Peach Orchard.

Sickles himself lost a leg in the battle and soon after retired from the army.

Dan Sickles, who had once killed a man namely, Barton Scott

Key, Francis’ son, and successfully pled temporary insanity, had nearly cost

the Union the day. By breaching the Union line, he’d made inevitable the

gruesome battles in The Wheatfield, Devil’s Den and The Peach Orchard. And by

forcing Meade to fill the gap in the line and support Sickles’ brave troopers,

who’d followed orders into a near-disaster, he’d left the Union center dangerously

vulnerable. Relief must have flooded through Union headquarters as the wounded

General Sickles was taken away on a stretcher, still nonchalantly puffing a

cigar. Yet, others argue that it was Sickles’ bravado that forced the Union to

fight so fiercely. In any event, both sides battered each other brutally on The

Second Day.

By about 10:30 PM the day's furious fighting came to an end.

“Old Pete” Longstreet, who’d gotten his men off to an excruciatingly late start

in the day but yet triumphed, described July 2nd as “the best three

hours fighting ever” by his troops. The Federals had lost ground during the

Rebel onslaught but still held the defensive position along Cemetery Ridge, which

they were reinforcing. Meade was determined to hold the center and throw the

remaining Confederates off Culp’s Hill.

Both sides regrouped and counted their causalities while the

moaning and sobbing of thousands of wounded men on the slopes and meadows south

of Gettysburg could be heard throughout the night under the blue light of a

full moon.

The second day of the Battle of Gettysburg saw horrific

casualties that outstripped the first day’s totals by far. The Union lost 1,500

men killed, and an astonishing 7,250 wounded. Like the Union, the Confederacy

had been badly bled this day as well, losing 1,175 killed and 5,325 wounded.

The combined two day casualty total of the battle thus far was fully 26,000.

Plum Run ran red with blood. The Wheatfield stank of bodies bloating and

bursting in the heat. Torn corpses were piled in Devil’s Den and lay neglected

under the blasted bare trees of the Peach Orchard. Snipers exchanged fire

across the face of Culp’s Hill, and Billy Yanks atop the Round Tops fired down

on Johnny Rebs who cursed and fired back. An eerie moan rose from the earth,

filling the air, horrifying forever all the men who lived to remember it.

Near the Seminary, Robert E. Lee planned his next day’s offensive. Convinced that the Union flanks were strong but that the Union center was weak, he planned a drive right through the copse of trees. It’s said that Longstreet and some others tried to dissuade him, but Lee was suffering from a peculiar lack of vision. He knew that Cemetery Ridge had been invested earlier in the day. He knew he could take it. While Lee’s grasp of the battlefield remained oddly static, Meade was reinforcing his previously soft centerline. The Third Day would tell.

On this day as well, Mary Todd Lincoln is forced to leap from the Presidential Carriage (in which she was riding alone at the time) to avoid a fatal accident. Mrs. Lincoln strikes her head on a rock. People later say that Mrs. Lincoln's behavior becomes erratic after the accident. She suffers terrible migraines for the rest of her days.

When the carriage is examined, it is found that several of the bolts holding the passenger seat in place have been removed, making the carriage a potentially deadly conveyance. Mary Todd Lincoln becomes convinced that the accident was no accident but a botched attempt at assassinating the President, though Mr. Lincoln downplays the incident.

When the carriage is examined, it is found that several of the bolts holding the passenger seat in place have been removed, making the carriage a potentially deadly conveyance. Mary Todd Lincoln becomes convinced that the accident was no accident but a botched attempt at assassinating the President, though Mr. Lincoln downplays the incident.

I find this analysis of Lee's tactical decisions to be very insightful.

ReplyDelete