JULY 18, 1865:

“Why did the South lose

the Civil War?” is a question that was probably first asked at Appomattox, and

it has likely been asked somewhere (along with its companion question, “Why did

the North win the Civil War?”) every day since.

There

is a whole library’s worth of books providing speculative answers, for, of

course, there is no one sure answer. It is probably accurate to say that all the answers ever debated were true

in one or another time, place, and circumstance. There are even those historians

who argue that although the Confederacy lost militarily it won philosophically,

and American history provides some evidence that even this idea has some truth.

Among

the most popular ideas (and this blog is not geared to go into great depth on

the subject) is that the South was simply overwhelmed militarily. Proponents of

this view point to the grand disparity between the Union’s population and

manufacturing base and the South’s. They forget, however, that the Confederacy,

starting with little more than the Tredegar Iron Works and the Gosport Navy

Yard, did manage to build a very respectable manufacturing infrastructure that

reached its high point in the Spring of 1864. They forget, largely because the

entire enterprise was destroyed in the last nine months of the war. They

forget, too, because the North’s manufactory capacity expanded during the war,

leaving the ratio of North / South

production unchanged.

The

South’s sudden growth in heavy industries was an economic miracle. In

everything relating to heavy industry except rail trackage, the South saw

tremendous growth between 1861 and 1864. The South also had a relatively healthy import-to-export balance until

the last months of the war, indicating that the Union blockade was extremely

porous. Other goods came from and through Mexico and the Caribbean. Ironically and illegally, the

United States itself was the Confederacy's primary trading partner. The South was

also able to use its limited resources to maintain vast well-equipped armies in the

field (toward the end of the war nitre for gunpowder

was leached from human excrement) and build a small but innovative navy (with the world’s first ironclad and

first successful battle submarine).

The

issue of Southern manpower shortages was a real one. At the South’s best it fielded

only 1 man for every 1.5 men the Union fielded. Had the South armed its slaves in

1863 or before it would have closed this gap. More damaging though, was the

percentage of Confederate combat soldiers to the overall population. The Confederacy saw

95% of its combat-age males fight. The Union saw 75% of its combat-age males

fight. The death and injury rates of combat sapped the smaller Southern

manpower pool at a far faster percentage rate than the North (though the North suffered greater overall numbers of casualties). Of the remainder of non-fighting men in the North, many were in war-related

industries, and this 5% to 25% disparity was one of the Union’s hidden

strengths.

There

is a wrongly-held belief that the South had better military men overall. The

facts do not bear this out. All the officers in both armies were graduates of

West Point (except for the mostly-incompetent political Generals with which

both sides suffered). The senior officers were almost all graduates of the

Class of 1846. Almost all the senior officers had honed their

fighting skills as young men in the Mexican War. Lewis Armistead C.S.A. and Winfield Scott Hancock U.S.A. had

been roommates at the Point. The Confederacy’s James Longstreet had been the Union’s Ulysses

S. Grant’s Best Man at Grant’s wedding. They, and many others, took the same

classes from the same professors, learned the same strategy and tactics, and

read the same books. For every overcautious Joseph Hooker of the Union there

was an overconfident John Bell Hood of the Confederacy. Both led their men into

disaster on the battlefield. Ineptitude was not solely a Northern disease.

Ambrose Burnside and Braxton Bragg were of a kind, and indeed Lieutenant

Burnside had served under Captain Bragg on the frontier in the 1850s. John Reynolds, who was considered the best Union field commander in 1863, and a match for Robert E. Lee, had been Lincoln's first choice to command the Army of The Potomac at Gettysburg. He turned down the honor of overall command, only to die on the first day of battle. Lee went on to lose at Gettysburg.

Likewise,

the idea that Confederates were somehow “born to the saddle” and were more than

a match for a Union full of “pasty-faced mechanics” was propaganda. While the

South had an initial and brief advantage in its line troops, battlefield losses

cut deeply into the “Cavalier Corps” of the Confederacy. By First Manassas

(Bull Run) in July 1861, the two sides were evenly matched, not least of all

because cadres of rugged Midwestern farm boys had already begun to swell the

Union ranks.

Southern

soldiers were not inherently better soldiers, nor did they have a greater sense

of duty than Northern soldiers. Desertion rates for both armies were about

equal until late 1864, when Dixie soldiers began leaving their posts in

ever-increasing numbers as the tide of the war shifted dramatically in the

Union’s favor. Despite Confederate rhetoric, then and now, Confederate soldiers

“swallowed the dog” quite often, swearing allegiance to the United States

readily when captured or paroled.

The

exception to this pattern was the Army of Northern Virginia, which was led by

Lee, Stonewall Jackson, and Jeb Stuart, and which, by late 1864 had thrown off

virtually all its deadwood. The men that remained were hardcore Confederates,

the crème-de-la-crème of the Southern fighting force, and utterly Spartan in their

abilities and expectations. The heroic but tragic retreat from Richmond was

evidence, if there ever was evidence, that in terms of esprit de corps the A.N.V. was likely the finest fighting force ever

assembled by man. And much of it was due to the judicious charismatic

leadership of Robert E. Lee.

|

| The "Mount Rushmore of the Confederacy" |

Robert

E. Lee is the apotheosis of Southern commanders and a paragon of Southern

manhood. But Lee’s beginnings in the war were unspectacular. A grandson-in-law

of George Washington, Lee was deeply conflicted about the Rebellion. His caution earned him the name “Granny Lee”

in 1861, and his decision to entrench around Richmond at the same time earned

him the derisive nickname “King of Spades.” Lee’s refusal to risk his men at

Cheat Mountain (West) Virginia almost relegated him to the dustbin of history,

after Jefferson Davis put him in charge of the inactive Military District that

comprised the Carolinas, Georgia, and Florida. Fortunately for the Confederate

cause, need saved him from oblivion. Lee was a man who inspired lesser men to greater acts, and he had an innate talent for discovering and developing other talented men. Thomas "Stonewall" Jackson and Jeb Stuart were great leaders in their day, and legendary now, but most of that was due to Lee's keen eye for leadership.

Lee

would probably not have had his impressive string of victories however, had the

United States been truly united on how to address the war. The North’s response

to secession was variable. Some citizens wished “the erring sisters to depart

in peace” while others wanted to preserve the Union at all costs. The idea of

conducting a civil war did not occur to most Americans until the South

Carolinians fired on Fort Sumter. That offense to the flag unified the North

and convinced nearly everyone that a military reaction was called for. Whether

that reaction was meant to punish the South, reunify the country, free the

slaves, or to be a signal protest was unclear.

General-in-Chief

George B. McClellan U.S.A. embodied this dilemma Having built a vast, effective

fighting force, he feared to risk it in battle. Perhaps his unwarranted

insistence that the Rebel armies outnumbered his armies was partly cowardice,

but it was also evidence of unwillingness to actually do the enemy any damage.

Instead, McClellan wanted a gigantic force that he could present in order to

strike fear into the Confederacy, forcing them to cower and return to the Union

--- but his Army of The Potomac was never quite big enough, the Confederates

were never quite frightened enough, and dramatic gestures were never quite

dramatic enough to cause the cowering that would lead to surrender. Instead,

when challenged, McClellan always backed down. And so the war ground on for months while

little was accomplished other than filling graves with young bodies.

Just

as McClellan never managed to land a decisive blow in the early years of the

war, neither did Robert E. Lee. The bloodlettings at Fredericksburg and

Antietam and other battlefields were terrible but they were hardly strategic.

It was not until Ulysses S. Grant became the Union’s General-in-Chief that the

war became a war and not just a string of essentially isolated, if gruesome, battles.

This

blog shows some evidence of that. Keeping in mind that not all Civil War

battles appear in the blog, between the attack on Fort Sumter and First

Manassas, a period of four months, sixteen battles are listed in the blog;

between First Bull Run in July 1861 and the beginning of the Peninsula Campaign

in April 1862, 60 engagements are listed --- 76 battles in just under a year.

In 1864, by contrast, the blog lists over 200 named incidents, ranging from

minor skirmishes to the bloody, week-long and endless Battle of Spotsylvania

Courthouse. In 1864, battle was continuous and strategic as opposed to

intermittent and tactical. In 1861,

battle was meant to punish the enemy; in 1864, to deplete his energy. Even

after Appomattox, the shooting war continued in small-scale actions for more

than a month. By the time the last gun was fired on June 28th by the

C.S.S. SHENANDOAH, the Union faced its opponent gasping for breath. The

Confederacy was down, not to rise again.

II

All

this is mere backdrop to the question we began with. After extensive study and

daily immersion in these blogposts, this blogger has a theory, not original,

that seems to answer the larger philosophical inquiry of Why the South lost the

Civil War.

Simply

put, the Confederates didn't want a "new" country; they wanted the

United States they were born in not to change. The Civil War was less a

“revolution” than it was a Confederate “counterrevolution” against an ever-more

diverse, Federally centralized, and industrialized Union. During the Presidential campaign of 1860, Abraham Lincoln was portrayed as a monstrous Abolitionist, which he was not. At most, Lincoln simply did not want slavery to spread into new Territories. But those who opposed him painted him with a satanic brush for their own purposes.

To a large extent, the image most Southerners had of themselves and of the South was

fantastic, a well-kept antebellum world of dashing gentlemen and ladies in crinoline, self-confident merchants an singing slaves. Southerners

deluded themselves, ignoring the grinding poverty and lack of opportunity most whites suffered, and they disregarded the corrosive effects of

slavery, which degraded men, both black and white.

At

the Montgomery Convention in February 1861, where a group of Planters,

politicians, and lawyers established the C.S.A., there was a strong contingent

that wanted to name the land "The United States of America" or

"The Southern United States of America."

The

Montgomery Convention copied the Constitution, the Bill of Rights, and the

Declaration of Independence, making changes that insured that their version of

the United States would remain a Jeffersonian and agrarian society.

|

| The first artist's rendering of "Tara" for "Gone With The Wind" (1939) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

In

Montgomery, they created two national holidays ---Washington's Birthday (for

they considered him the father of their

country) and the Fourth of July, in honor of the Patriots who had fought, bled

and died for liberty in 1776.

George

Washington appeared on the Confederate Great Seal, on currency, and on stamps.

Thomas Jefferson and Andrew Jackson too appeared on their currency. Virginia,

the “Mother of Presidents” became the site of their permanent capital city, a

building designed by Jefferson their Capitol.

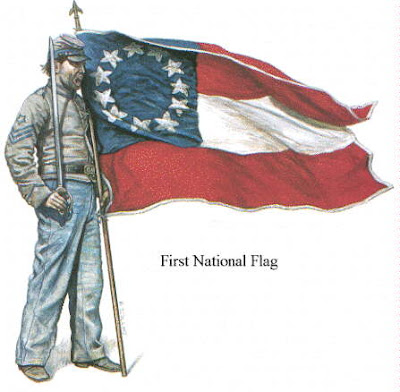

The

first national flag of the Confederacy, the Stars & Bars, was so similar to

the Stars & Stripes that they were often confused across a battlefield.

Their

enemy was not the United States but Yankees,

a strange and alien race that had somehow seized control of the land they loved. And though they spoke (and some still speak)

of “Southern heritage,” it is this blogger’s opinion that that "Southern

heritage" doesn't exist; it is quintessentially the heritage of all

Americans.

Several

historians have posited the thought that the southern United States had a

firmer grasp of its own “nationhood” than other parts of the country (based

largely on the existence of human bondage in the south), but upon closer

inspection, this theory does not hold up. During the War of 1812, it was New England that threatened secession

over economic issues. As the nation grew, voices in the Midwest and the Far

West called for the establishment of various independent States for one reason

or another.

|

| During the War of 1812, New England debated secession at Hartford, Connecticut, but the war ended before the issue came to a vote |

Although

some argued then (as some argue now) that the war was about “States’ Rights” or

“economics” or a dozen other reasons, the war was about slavery and the fear that

the “Peculiar Institution” would vanish, especially if it was not allowed to

spread to new areas. From the Cornerstone Speech onward, slavery (and its concomitant, the superiority of the white race) underlay

the entire Confederate enterprise. At the end of the war, when even Jefferson

Davis saw Emancipation as part and parcel of maintaining the nationalism of the

Confederacy, vocal opponents declared that the “crown would be worthless

without its jewel” and that they “did not love their country enough” to fight

if fighting meant that blacks were to be their comrades-in-arms. These are

simple, documented, indisputable facts.

Yet,

it must be acknowledged, slaveholders in the Union States of Kentucky,

Delaware, Maryland, and Missouri fought under the Union flag, so while the war

was about slavery, that was clearly not the only issue in dispute; nor was it

an irreconcilable issue that inevitably had had to lead to war.

The

South went out of the Union on a tide of fire-eating rhetoric, led by men like

Edmund Ruffin, Barnwell Rhett, and William Lowndes Yancey, who monopolized the

national debate in late 1860 and early 1861. Literally as soon as these men

accomplished their goal of forcing secession they were relegated to the back of

the top shelf in the Confederate closet. While most of the men who called for (and

attended) the various State secession conventions followed in the fire-eaters’

steps, they adopted positions that were far more moderate than might be

expected.

In

State after State, the secession conventions followed a pattern: Small groups

of 100 or so self-appointed delegates, often unelected to any public office,

would gather, pass a resolution, and then push it on the State Legislatures.

Most of the secession delegates were wealthy slaveowners. Most had excellent

political connections. Most did not represent

a particular constituency. Some were not even natives or full-time residents of

their States. The fire-eaters spoke, were silenced or bought off with sinecure

positions, and the delegates essentially recreated the same State systems that

had existed for 85 years under the old Union.

|

| White Southern sharecroppers in the 1930s |

By

and large, the needs, wants, opinions, and expectations of the majority of the white

population did not enter into the secession calculus even though they provided

the bulk of the armed forces. Poor, struggling, and without wealth in slaves, to

most citizens of the Confederacy the replacement of the Stars and Stripes with

the Stars and Bars made little initial difference in their lives. It was an era

without Federal taxes and services other than the Post Office, and the new flag

looked familiar enough to be comforting to most local residents. Southern Unionism existed, but it was often

violently suppressed or lived in an uneasy truce with Confederate patriotism.

Had

Jefferson Davis not pressed the issue of the status of Fort Sumter --- an

attack R.M.T. Hunter prophesied would be “fatal” --- it is likely that

secession would have triumphed, that most Americans would have chosen to avoid

war, that the Confederacy would have established itself, and that hard-and-fast

Unionists like President Lincoln would have been a loud, ineffectual, minority.

Or, if the secessionists had simply bided their time, Lincoln would likely have

been voted out in 1864, and the issue of slavery would have continued to

bedevil the United States well into the Twentieth Century.

III

But

war came. It was an unequal contest from the start. The North was frenzied due

to the violation of the flag at Sumter, while the South despised the invasion of its

territory. Still, it is questionable if the men who fought and died in the

beginning days of the war really had a firm grasp of what they were fighting for. Southerners marching to battle sang Hail, Columbia! and Dixie and so did their Northern fellows. And The Battle Cry of Freedom with two sets of lyrics.

The finding of a moral rationale for the war --- Emancipation --- tended to

strengthen and unify the Northern war effort (Northern anti-emancipationists

became identified with the South).

In response, much of the Southern cause

therefore had to be predicated upon the idea of white racial supremacy and the

fear of loss of privileged status, even among poor whites who only believed they had such status.

|

| This was the symbol of the Alabama Democratic Party from 1877 until 1966 |

The

South, however, lacked a correspondingly high moral rationale for the war, a simple, easily graspable concept. Although some

Southerners came to believe they were fighting to “preserve their way of life,”

most Southerners had little or no investment in the actual perpetuation of the

Planter Class or of slavery per se. Many

Southerners fought for the amorphous reason that “Y’all are down here.” At the same time, as early as the Autumn of

1861, the South was suffering shortages that would eventually doom it.

|

| A bread riot in Mobile, Alabama |

At

the same time, the United States continued to expand both territorially and

economically during the war and despite the war. Three new States (including

Kansas in early 1861) were admitted to the Union under the shadow of war. New

territories were organized. Rails were laid. Immigrants continued to come from across the seas. The

Union’s economy burgeoned. None of this could be said of the South.

|

| Chinese laborers building a western rail line |

The

North in short, had adopted a set of clearly definable war goals, while the South

was fighting (a war it had begun) to maintain a status quo in which most of its

soldiers stood to gain little. With fewer resources and fewer fighting men, the

cost of the war would eventually overwhelm the newborn Confederacy.

IV

Among

the great errors made by the Confederacy, its foreign diplomacy, or, rather lack of foreign diplomacy, was a critical if widely overlooked element in its loss of the war.

Literally

from the very beginning, Confederate foreign policy was a catalogue of

disasters. Beginning on the December day in 1860 when three “Confederate

Commissioners” visited President James Buchanan demanding U.S. recognition of

the “Republic of South Carolina” and promising war when recognition was not

immediately tendered, the Confederacy’s handling of international affairs was

simply --- stupid.

The

immediate imposition of an untested, unsolicited cotton embargo to force the

European powers to recognize the South led the various nations of Europe to

seek out other sources of cotton. Instead of knuckling under to “King Cotton” Great

Britain began cultivating cotton in India and Egypt, forever undoing the

South’s total monopoly on the plant.

And

though “Southern Commissioners” (they never called themselves “Ambassadors”)

were very successful at coopting the upper classes of the U.K., France, Prussia, and Russia to their

side, largely by presenting Southerners as a well-placed oligarchy on par with

European nobility, the Confederacy failed utterly in winning over the much more

numerous bourgeoisie of those countries. As a result, not one nation of

consequence chose to afford the Confederacy international recognition.

Southern

diplomacy was almost entirely focused on obtaining war materiel in exchange for

cotton. Had the South managed just a simple standing trade agreement (along the

lines of what the U.S. and Taiwan enjoy today), that may have opened the door

to other advantages. But it never happened.

It

never happened, by and large, because Confederate President Jefferson Davis,

the former U.S. Secretary of War, failed to view the Civil War as anything but

a military conflict when it was in fact, a political conflict first and

foremost. Where the Confederacy left voids in politics, the Union rushed to

fill them, managing, over time, to determine the scope and scale of the

Confederate war away from the battlefield. And since the decisions made in international

politics could not help but affect the decisions made on the domestic front,

the Union slowly garroted the Confederacy through the genteel but vicious

mechanisms of hundreds of State Dinners, whiskey tumblers, and informal poker

games. The Union also exploited, to great effect, the evils of slavery, claims

which the South could only weakly counter.

If

the South’s Foreign Affairs were chaotic, its Domestic Affairs were just as

chaotic. By altering the Constitution, the Confederacy had effectively

reinstated the old Articles of Confederation, in which a hodgepodge of

quasi-independent States could only act in unison, or more likely fail to act

at all. More than once during the Civil War, Jefferson Davis bemoaned the fact

that he did not have the ability to invoke the kinds of Constitutionally

unstated but implicit War Powers that Abraham Lincoln drew upon (the Powers

alluded to may or may not have existed or been intended to exist, but Lincoln

assumed them in order to preserve the Union). Davis, with his far less flexible

Constitution, could not do that. Davis also had to cope with eleven State

Governors, each of which assumed himself the President of a small republic. As

the various Governors squabbled with one another, and with Davis, the

Confederacy unraveled. Arguments about whether Mississippi troops could fight

in Arkansas --- or should fight in Arkansas --- were not unusual. Such internal

disputes gave the lie to the idea that the Confederacy had some particular

claim on “nationhood.”

V

In

a September 22, 1861 letter to Orville Browning, President Lincoln wrote of his

birthplace State, “I think to lose Kentucky is nearly the same as to lose the whole game.

Kentucky gone, we cannot hold Missouri, nor, as I think, Maryland. These all

against us, and the job on our hands is too large for us.”

Lincoln

intuitively understood that Kentucky was the linchpin of the Union, and did

everything he could --- including tolerating the secesh sympathies of its

Governor, Beriah Magoffin, who declared his State “neutral” in the conflict,

but then gave every advantage to the South --- to keep Kentucky in the Union.

Lincoln

was right. Without the “Border State” of Kentucky in the

Union, the Confederacy would have had a free hand to carry the war into the

Southern-leaning butternut counties of Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio. West

Virginia would probably have fallen back into Confederate hands, the Wheeling

panhandle sticking like a dagger into the North. In badly-split Missouri, Unionists would have been all

but isolated. The Confederacy would have controlled the Ohio River watershed

and a crucial stretch of the Mississippi. Almost certainly, “the whole game”

would have been up. And though Kentucky

sent a large number of men to the Union (100,000) it also sent a

not-insignificant 24,000 to the Confederacy, and had rival North / South

governments.

Amazingly,

however, Jefferson Davis never said the same about Tennessee. Tennessee,

however, was the Confederacy’s Kentucky. Tennessee provided approximately

190,000 men to the Confederacy and 50,000 to the Union. Like Union Kentucky with a rival Confederate government, Confederate Tennessee had a rival Union government.

|

| Fort Donelson |

Trisected

by rivers, Tennessee and Kentucky are truly sister States, sharing a lomg

common border, sharing a joint subculture, sharing landforms, and sharing a

centralized location that makes them both accessible to the southern North and

the northern South.

|

| Shiloh Church |

Who

controlled Kentucky controlled the Union. Who controlled Tennessee controlled

the Confederacy.

|

| Stones River |

And

so, it is telling that there were only eleven major battles in Kentucky during

the war, but there were 38 major battles in Tennessee. There was no cogent

Confederate strategy to hold Tennessee, but there was a cogent Union strategy

to take it. Taken it was, the last State to leave the Union in April 1861

and the first reconstructed back into the Union in February 1862. And though

fought over violently, with endless small engagements, several major campaigns,

and critical battles such as Fort Henry, Fort Donelson, Shiloh, Stones River,

Lookout Mountain, and Fort Pillow, the Confederacy never won back enough

Tennessee land to politically control the State again. Although Virginia, with its

proximity to the two national capitals saw more battles, Tennessee proved to be

the wedge that ultimately shattered the Confederacy.

VI

So,

why did the South lose the Civil War? Perhaps because in the end, the South lost the war because the South

never wanted to be another nation, it

wanted to be the nation. The

Confederate States of America found itself in battle with its Mother Country, a

country it wished to emulate, a country based upon not upon identical

principles but upon the very principles

Southerners held dear, while sharing heroes and cultural symbols with that

country. All this set up in the minds of Southerners a cognitive dissonance

that, in the end, would not allow

them to defeat the United States of America. In the end, for better and worse,

they were, and remain, part of one America.