FEBRUARY 18, 1865:

The fall of Charleston:

|

| The last palmetto in Charleston, February 1865 |

As the sun rises over

South Carolina, a bitter black pall hangs over the State, rising from what had

been its proud capital city. After a night of destruction worthy of The

Chronicles of The Barbarians, there is near nothing left of Columbia.

David Conyngham, a

Columbia resident, memorializes the scene:

The 18th of February dawned upon a city of ruins . . .

Nothing remained but the tall, spectre-looking chimneys. The noble-looking

trees that shaded the streets, the flower gardens that graced them, were

blasted and withered by fire. The streets were full of rubbish, broken

furniture and groups of crouching, desponding, weeping, helpless women and

children . . . That long street of rich stores, the fine hotels, the

court-houses, the extensive convent buldings, and last the old capitol, where

the order of secession was passed...were all in one heap of unsightly ruins and

rubbish.

Heartbreak today shall

be the handmaiden of disaster, as indomitable Charleston strikes its colors

just as day breaks.

With the withdrawal of

General P.G.T. Beauregard’s city garrison troops toward North Carolina and the

cutting of the city’s overland link with Columbia, Charleston, South Carolina,

“The Cradle of Secession” surrenders to Union troops under Prussian-born General

Alexander Schimmelfennig.

Fearing that General

Sherman will head east to burn Charleston, the City Fathers choose to submit to

Schimmelfennig,

the leader of the Union’s longtime regional ground assault against the city,

but implore him not to burn Charleston to the ground. When Schimmelfennig

surveys the blasted city he agrees to leave it as it is. Thus, a few of

Charleston’s magnificent live oaks and a handful of its shell-pocked antebellum

homes survive the war, as does a single palmetto.

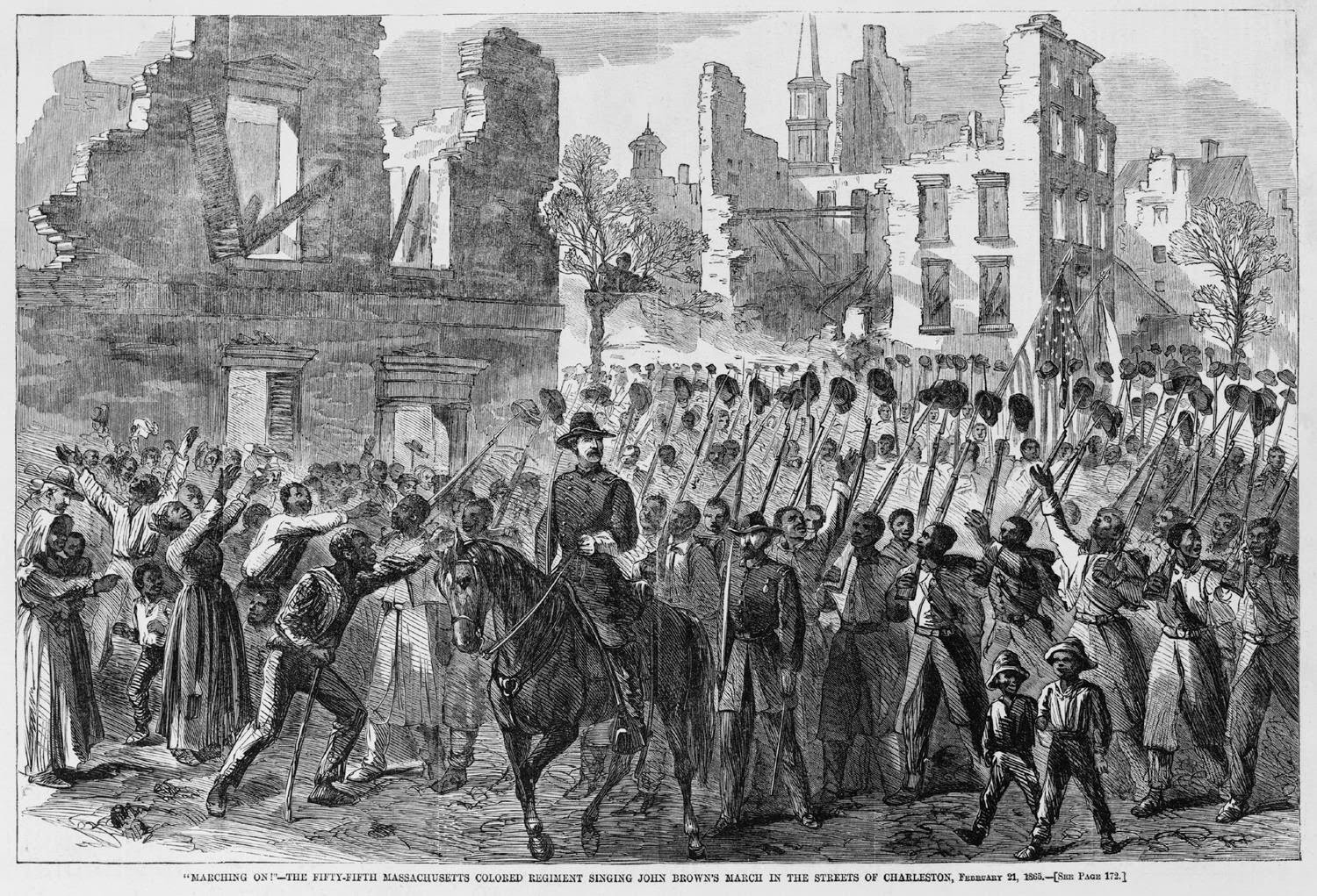

The 55th

Massachusetts Regiment (U.S.C.T.) is the first Union force to enter the city.

Made up of many former slaves from South Carolina, and from Charleston

particularly, the men of the 55th were told they must keep in their

ranks, but they could “shout and sing as they chose.” Many of the men discover

relatives in the city and emancipate brothers, sisters, parents, kith and kin.

The task of the 55th

Massachusetts quickly turns to firefighting, putting out myriads of small fires

set by Confederates determined to burn what little is left of the city.

The city is a heap of ruins,

its downtown having burned in late 1861, and its environs having been daily

bombarded by a combined Union land-sea assault every day since the Battle of

Gettysburg.

It has been a long time

since heavily-blockaded Charleston has contributed significantly to the South’s

Civil War effort, but the city is far more important as a symbol: It is the

Confederacy’s Lexington and Concord; and its implacable resistance to the

Union’s unending attacks have made it into the beating heart of Confederate

resistance and willpower.

Now that heart is

stilled. The cradle has fallen.

|

| The Charleston Armory |

The Union quickly

broadcasts news of Charleston’s surrender worldwide. As word of Charleston’s

fall spreads throughout the States of America and beyond, the North rejoices;

the South grieves. Most Unionists realize that victory is upon them. Most

Confederates recognize defeat.

The Mobile Register laments:

The people are not whipped but cowed. Their souls and not

their hands are disarmed. Our strength is, not sapped, but our courage is

oozing out at the ends of our fingers.

A fresh rash of “French

leaves” strikes the remaining Confederate forces, shrinking the already

shrunken armies even more. Throughout the South people begin quietly to feed

their Stainless Banners and portraits of Jefferson Davis to their fireplaces

and stoves, though portraits of Robert E. Lee are lovingly packed away in attic

trunks.

In the Border States and

in areas Reconstructed or restored to the Union, Southron patriots have not

been quiescent. Although armed resistance has been proven futile in most places

and in most hearts and minds, the until-recently Confederate citizenry of such

regions have refused to give up all hope of a Confederate resurgence. Many have

been waiting for the war to take another of its inexplicable turns as it did in

the Summer of 1864. Incidents of minor sabotage have not been uncommon. Civil

Resistance to Union edicts has not been unknown. Non-cooperation with Union

officials has been widespread. Ordinary rudeness has been a method of rebel

expression toward Union representatives, even the local postmasters. Excessive courtesy is a sign of hateful

disdain. (Confederate women are particularly adept at such behavior, even to

this day. Ask any Southern belle what “Bless your heart” really means and you will be answered by a sly chuckle or a wall-shaking

guffaw.) With the collapse of South

Carolina, the resisters in the North, most of them, silently give up.

In some areas of the

Confederacy the shift back to Unionism is sudden, dramatic, and violent.

Nowhere is it more so than in Loudoun and Fauquier Counties in Virginia,

“Mosby’s Confederacy.” The area, nominally Union-held since just after Fort

Sumter, has been a flaming hotbed of Confederate nationalism throughout the

war, allowing Mosby’s Rangers to operate unchecked throughout the region.

As the fortunes of war

changed in the Fall of 1864, Mosby was forced to impose taxes in-kind --- food,

cloth and other necessaries --- on the loyal citizens of his little Confederacy.

Few balked at first, but the hard winter of 1864-65, and the scorched earth

policy imposed by the Union upon much of Mosby’s Confederacy from November 28th

to December 2nd has made the tax in kind nearly impossible to pay. Mosby’s men

have been reduced to scavenging and raiding their own stalwarts, a state of

affairs that has turned many of the struggling locals against Mosby. A small-scale

civil war amidst the larger Civil War breaks out in Mosby’s Confederacy, a

battle between the local Unionists and hungry Confederates on one side, and

die-hard Confederate patriots on the other. Mosby’s position is worsened by the

fact that those who pledge allegiance to the United States have their barns

rebuilt, their livestock replaced, and food freely delivered by the Federal

troops in the area, a Hearts & Minds policy that Mosby cannot hope to match.

More and more often, his men find themselves bivouacking in the shadow of the

Blue Ridge Mountains rather than, as formerly, in the once-common safe houses

in his Confederacy.

Harper’s Weekly sounds a clarion call:

That Charleston should fall was inevitable. That Charleston

should fall without a blow was inconceivable . . . If there were any possible

last ditch it was the streets of Charleston . . . It has been considered,

indeed, the special seat of rebellion. It has always been a nursery of treason

. . . It was a strange scene on that April day four years ago. The spectators

cheered and wept for joy, and the merry bells rang, when the flag of their

country fell for the first time, shot down by its own children. Did the

spectators of that day remember it when at last that flag returned triumphant?

Over how much bitter agony, through what seas of costly blood, across what

blighted hopes and ruined lives it returned; but also over the desolation of

Carolinian homes which Carolina has wrought; over the wide waste of fortunes

which Carolina has destroyed; over the treacherous doctrine of State supremacy which

Carolina has hugged snakelike to her breast; over the relics of slavery which

Carolina has abolished. The old flag returns. Peace, union, and prosperity are

the benedictions it imparts . . .

|

| St. Michael's Church, February 1865 |

|

| St. Michael's Church, February 2015 |

|

| Today's Historic District |