APRIL 21, 1865:

“I feel incompetent to perform duties so

important and responsible as those which have been so unexpectedly thrown upon

me." --- President Andrew Johnson*

I

After

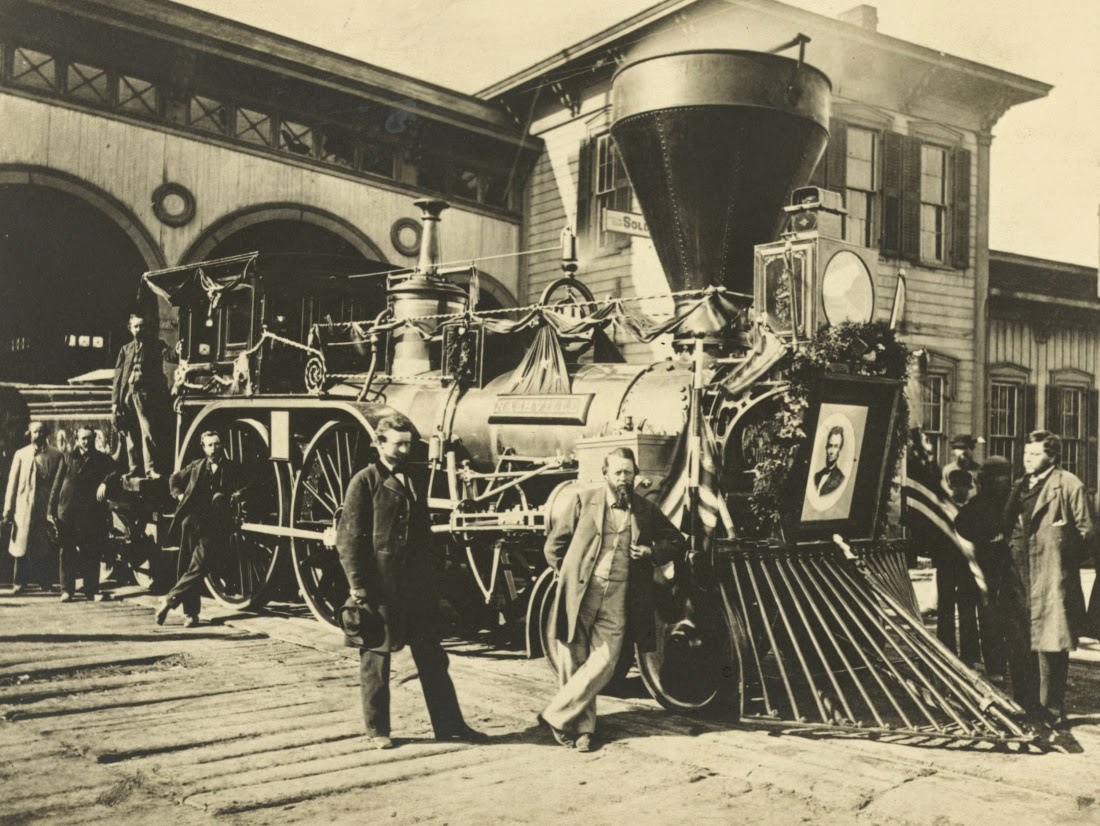

a brief final service at the Capitol Rotunda, Abraham Lincoln’s body is placed

aboard a special train designated to return Lincoln to Springfield, Illinois

for interment.

The

coach carrying Lincoln in his casket is also carrying the body of Willie

Lincoln, who had died of Typhoid in 1862 during his father’s Presidency.

The Funeral Train was comprised of a lead locomotive and tender that preceded the actual consist and made sure the track was clear for passage, plus a locomotive and tender (“Old Nashville”) painted and draped all in black pulling nine cars, including the hearse car, the family car, the honor guard car (made up of members of the Veterans’ Reserve Corps and several U.S. Major Generals), and a luggage car. All told, 300 passengers accompanied Lincoln’s body back to Illinois. Mary Lincoln was not among them. Today, in fact, was the first day since the assassination that Mary had even sat up in bed.

The train was scheduled to cover a route some 1,654 miles long through the States of Maryland, Pennsylvania, New Jersey, New York, Ohio, Indiana, and Illinois. The train was scheduled to pass through two hundred and eight towns and cities along the route, which approximated the same route Lincoln had taken from Springfield to Washington D.C. in 1860.

At each stop, Lincoln’s coffin was taken off the train, placed on an elaborately decorated horse-drawn hearse and led by solemn processions to a public building for viewing. In cities as large as Columbus, Ohio, and as small as Herkimer, New York, thousands of mourners flocked to pay tribute to the slain president. In Philadelphia, Lincoln’s body lay in state on in the east wing of Independence Hall, the same site where the Declaration of Independence was signed. Newspapers reported that people had to wait more than five hours to pass by the president’s coffin in some cities.

In

towns where the train did not stop crowds gathered at the local railroad

station to pay homage to the train as it chugged slowly through. Along open

stretches of track farm families and local residents stood along the

right-of-way often dressed in black, often weeping, and almost always waving

small American flags as the late President passed by.

On

this particular day, short stops were made at Annapolis Junction and Relay

Station before the train arrived in Baltimore, 38 miles from Washington. Unlike

Lincoln’s first, surreptitious passage through Baltimore in 1860 when an

assassin was feared to be abroad, the assassinated President’s remains were

welcomed with solemn honor into the city. It was 10:00 A.M. when Mr. Lincoln's

coffin was borne to the Merchant's Exchange Building, where it was opened to

the view of approximately 10,000 people for three hours. A memorial service was

held for the slain President.

The train departed at 3:00 P.M., destined for Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. After the 58 mile trip the Lincoln Funeral Train arrived in the Pennsylvania capital at 8:00 P.M. The coffin was then carried by hearse to the state House of Representatives, placed in a catafalque, and opened for public viewing at 9:30 P.M. A funeral service was held.

II

While

his victim moved slowly toward his last resting place John Wilkes Booth was

going nowhere. Having made landfall on the Maryland side of the Potomac after

his botched attempt at crossing the river into Virginia, Booth (and David Herold)

holed up in a fisherman’s shack along silty Nanjemoy Creek that was owned by John

J. Hughes. Hughes was (coincidentally or not) an acquaintance of Herold’s.

Hughes gave the two men a meal, and studiously ignored their existence for the

almost two days they remained hidden there.

III

Having

received his Orders from Robert E. Lee to “go home,” Colonel John S. Mosby

called his Rangers together in the small town of Salem, Virginia.

Rather

than surrender to the local Federal authorities (who considered his men

bushwhackers and undeserving of the parole terms offered by Grant to Lee),

Mosby simply ordered his unit, formally the 43rd Battalion, Virginia

Cavalry, to disband peaceably. In a small, but moving ceremony, the usually

stoic Mosby wept as he made sure to shake every soldier’s hand. He then

delivered the following farewell address:

Soldiers:

I have summoned you

together for the last time. The vision we have cherished for a free and

independent country has vanished and that country is now the spoil of a

conqueror. I disband your organization in preference to surrendering it to our

enemies. I am no longer your commander. After an association of more than two

eventful years I part from you with a just pride in the fame of your

achievements and grateful recollections of your generous kindness to myself.

And now at this moment of bidding you a final adieu accept the assurance of my

unchanging confidence and regard.

Farewell.

The

“Gray Ghost” went on to have a rather remarkable post-war career. Trained as a

lawyer, he returned to that practice for awhile, then wrote a fascinating and

popular reminiscence of his partisan unit. He also --- almost blasphemously ---

became a Republican after the war, campaigning actively in the South for

Ulysses S. Grant’s Presidency. Threats to his life from fellow Southerners spurred

President Grant to name him U.S. Envoy to Hong Kong. He later became a U.S.

Prosecutor. Always an opponent of slavery (he had come from a poorer family) he

overcame his learned prejudices and advocated for Civil Rights in the early

1900s. He was a friend of the Patton family, and played soldier with young

Georgie Patton, who would become renowned during World War II.

Mosby

died in Washington D.C. in 1916.

IV

General

William Tecumseh Sherman’s “Memorandum, or Basis For Agreement” of April 18th,

the document that lay out the terms of surrender for General Joseph E. Johnston

C.S.A., was a liberal document even by Confederate terms.

Far

more expansive than the terms Grant offered Lee at Appomattox, the “Memorandum”

even encroached upon the prerogatives of the Federal Government as outlined for

Grant by President Lincoln in early March.

In

that outline Lincoln had stated very explicitly that Generals were “not

to decide, discuss or confer upon any political question.”

There

was just one problem: Sherman never got

the memo. Literally. He was marching. And no one had thought to send him a copy

before he met with Johnston. With the best of intentions, Sherman walked into a

firestorm. His “Memorandum” contained, among others, the following provisions:

• The Confederate armies now in existence to be disbanded and

conducted to their several State capitals, there to deposit their arms and

public property in the State Arsenal; and each officer and man to execute and

file an agreement to cease from acts of war, and to abide by the action of the

State and Federal authority. The number of arms and munitions of war to be

reported to the Chief of Ordinance at Washington City, subject to the future

action of the Congress of the United States, and, in the mean time, to be used

solely to maintain peace and order within the borders of the States

respectively.

In effect, Sherman meant

to allow the Confederate armies to surrender “in place”; to retain their

weapons, and to submit themselves to their own State, rather than Federal,

authorities.

Whether by design or

chance (and it should be remembered that John C. Breckinridge the Confederate

Secretary of War was involved in working out these terms) the idea of the

armies submitting to State authorities was essentially identical to an idea

broached by General E. Porter Alexander C.S.A. to General Lee when the two men

discussed the possibility of surrender just before Appomattox.

• The recognition, by the Executive of the United States, of

the several State governments, on their officers and legislatures taking the

oaths prescribed by the Constitution of the United States, and, where

conflicting State governments have resulted from the war, the legitimacy of all

shall be submitted to the Supreme Court of the United States.

This provision too, had definite

echoes in it of the “Virginia Plan” presented by Assistant Confederate

Secretary of War John A. Campbell (Breckinridge’s immediate subordinate), to

President Lincoln while Lincoln was in Richmond. A vociferous rarely-united Cabinet had finally

forced Lincoln to see the folly of recognizing the Confederate State

governments even for limited purposes.

It is quite possible that this too was an intentional insertion on

Breckinridge’s part.

and

• The people and inhabitants of all the States to be

guaranteed, so far as the Executive can, their political rights and franchises,

as well as their rights of person and property, as defined by the Constitution

of the United States and of the States respectively.

In its discussion of

“property” Sherman’s “Memorandum” failed to address slavery at all, leaving the

door wide open for destructive, even fatal, debates.

Was

Sherman bamboozled by Breckinridge at their Bennett Place meeting? Or was this

his own view of the Union restored? Either way, the “Memorandum, or Basis For

Agreement” would have a very short life.

It

is easy to imagine President Lincoln reading over Sherman’s “Memorandum” with

bemusement (or even amusement), and then telling a homely story about a blind

goatherd while delivering a written rap on the knuckles to his fire-haired

general who was so clearly desirous of peace.

There

was only one problem. Lincoln was dead. And if his voice was still whispering

in corners of the Cabinet Room, nobody was listening.

V

The

Cabinet Room was in an uproar.

President

Andrew Johnson was enraged at General Sherman for his effrontery in making

political decisions. Quite ironically (for Johnson was a Unionist southerner)

he reminded his Cabinet of Sherman’s long associations in the south, and how

this rendered the man untrustworthy.

Other

voices were raised, especially Edwin Stanton’s.

---

What if Sherman is planning a coup d’etat?

---

Perhaps he’s marching on Washington even now . . .

---

Maybe he has joined forces with Johnston!

---

You know he has a reputation as a madman.

Someone

finally recommended conferring with General Grant. While Grant’s arrival was

being awaited, Stanton wrote out Orders relieving Sherman of command and

putting Grant in charge of the Army of The Tennessee. Sherman was to be arrested.

That started another round of panicked shouting.

Attorney

General James Speed asked, “What if Sherman

arrests Grant?”

---

Send the Army of the Potomac to challenge the Army of The Tennessee!

---

Have Sherman tried for treason.

By

the time Ulysses S. Grant met with the Cabinet, the men around the table were

in a deadly mood.

Grant

paled as he read the Orders he was handed, and he shook inwardly as he listened

to each of the Secretaries in turn, and to the President.

Grant,

no less than anybody else, was emotionally exhausted and brimming with anger

over the death of President Lincoln. But he realized that the men in the

Cabinet room were not just exhausted and angry, they were also dangerously

emotionally overwrought. Bill Sherman’s neck was being fitted for a noose by

the men around the table, and Grant knew that unless he handled the next few

minutes with extreme care, he would most likely be swinging alongside Sherman.

The tact and diplomacy he exhibited in the Cabinet Room that day had no

third-party witnesses, but it undoubtedly equaled --- perhaps surpassed ---

anything Grant had accomplished at the McLean house on the ninth.

He

quietly assured the angry Executive that Sherman was eminently trustworthy,

that he was Grant’s own personal friend, and that he was not crazy.

---

I trust Sherman with my life. He is a stalwart Unionist.

President

Johnson was still snarling --- So how do you explain this? --- meaning the

Memorandum.

---

I promise you I will get to the bottom of it.

Grant

convinced them all that he would not need The Army of The Potomac to handle

Sherman. Right now, he reminded everyone, we need men to find the President’s

killer. I will go with my usual detail; and I will meet with Bill Sherman

alone.

When

Grant left the Cabinet Room to prepare for his trip to North Carolina, to his

credit it was a far calmer place than when he had entered.

* “I feel incompetent to perform duties so

important and responsible as those which have been so unexpectedly thrown upon

me" was a line from newly-inaugurated President Andrew Johnson's first public pronouncement upon becoming President. It is impossible to imagine today --- and it must have been nearly impossible even then --- to imagine a Chief Executive who came to the White House by way of his predecessor's assassination saying "I feel incompetent" in the midst of a national tragedy and a bloody Civil War. It certainly did not inspire confidence, promote calm, or soothe the battered emotions of anyone. Johnson was the first President to be impeached, and it is not difficult to see how he trod the path toward impeachment, especially given the high-strung public atmosphere of his time.