MAY

1, 1865:

“Love is a rare attribute in the chief

magistrate of a great people” --- Reverend P.D. Day

I

The U.S. Government establishes

a Military Tribunal (the Hunter Commission) to try the accused conspirators in

President Lincoln’s assassination. Although Civil Libertarians object, the

newspapers question whether the United States is a military dictatorship, and

leading jurists question its Constitutionality, most (northern) citizens are

disinterested in such legal blather. They simply want to miscreants to hang.

President Johnson’s Executive

Order and (excerpts from) Attorney General James Speed’s carefully crafted (oddly

postdated), tautological, and torturously reasoned justification appear below:

Order

of the President

PROCEEDINGS

OF A MILITARY COMMISSION,

Convened

at Washington, D.C., by virtue of the following Orders:

{Executive

Chamber Washington City, May 1, 1865.}

WHEREAS, the Attorney-General of the United

States hath given his opinion:

That

the persons implicated in the murder of the late President, Abraham Lincoln,

and the attempted assassination of the Honorable William H. Seward, Secretary

of State, and in an alleged conspiracy to assassinate other officers of the

Federal Government at Washington City, and their aiders and abettors, are

subject to the jurisdiction of, and lawfully triable before, a Military

Commission;

It is ordered:

1st That the Assistant Adjutant-General detail

nine competent military officers to serve as a Commission for the trail of said

parties, and that the Judge Advocate General proceed to prefer charges against

said parties for their alleged offenses, and bring them to trial before said

Military Commission; that said trial or trials be conducted by the said Judge

Advocate General, and as recorder thereof, in person, aided by such Assistant

and Special Judge Advocates as he may designate; and that said trials be

conducted with all diligence consistent with the ends of justice: the said Commission to sit without regard to

hours.

2d.

That Brevet Major-General Hartranft be assigned to duty as Special

Provost Marshal General, for the purpose of said trial, and attendance upon

said Commission, and the execution of its mandates.

3d. That

the said Commission establish such order or rules of proceedings as may avoid

unnecessary delay, and conduce to the ends of public justice.

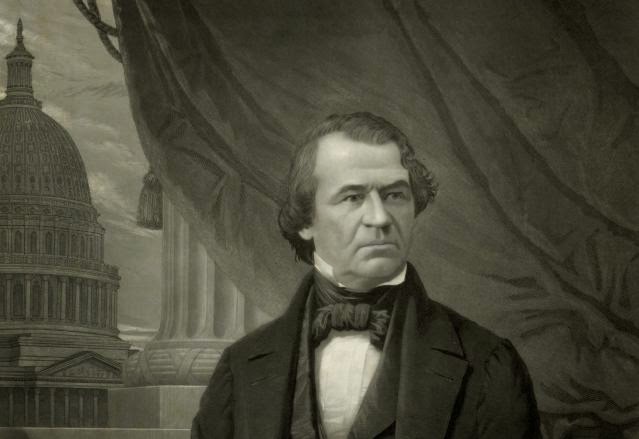

[Signed]

ANDREW

JOHNSON

***

OPINION

ON THE CONSTITUTIONAL POWER OF THE MILITARY

TO

TRY AND EXECUTE THE ASSASSINS OF THE PRESIDENT.

BY

ATTORNEY GENERAL JAMES SPEED.

ATTORNEY

GENERAL'S OFFICE

Washington,

July — , 1865.

SIR:

You ask me whether the persons charged with the offense of having assassinated

the President can be tried before a military tribunal, or must they be tried

before a civil court. The President was assassinated at a theater in the city

of Washington. At the time of the assassination a civil war as flagrant, the

city of Washington was defended by fortifications regularly and constantly

manned, the principal police of the city was by Federal soldiers, the public

offices and property in the city were all guarded by soldiers, and the

President's House and person were, or should have been, under the guard of

soldiers. Martial law had been declared in the District of Columbia . . .

Such

being the facts, the question is one of great importance— important, because it

involves the constitutional guarantees thrown about the rights of the citizen,

and because the security of the army and the government in time of war is

involved; important, as it involves a seeming conflict between the laws of

peace and of war.

Having

given the question propounded the patient and earnest consideration its

magnitude and importance require, I will proceed to give the reasons why I am

of the opinion that the conspirators not only may but ought to be tried by a

military tribunal.

A

civil court of the United States is created by a law of Congress, under and

according to the Constitution . . . A military tribunal exists under and

according to the Constitution in time of war. Congress may prescribe how all

such tribunals are to be constituted . . . Should Congress fail to create such

tribunals, then, under the Constitution, they must be constituted according to

the laws and usages of civilized warfare . . . I do not think that Congress can, in time of

war or peace . . . create military tribunals for the adjudication of offenses

committed by persons not engaged in [warfare] . . . But it does not follow that

because such military tribunals can not be created by Congress . . . that they

can not be created at all . . .

That

the law of nations constitutes a part of the laws of the land, must be

admitted. The laws of nations are expressly made laws of the land by the

Constitution, when it says that "Congress shall have power to define and

punish piracies and felonies committed on the high seas and offenses against

the laws of nations." . . . No one that has ever glanced at the many

treatises that have been published in different ages of the world by great,

good and learned men, can fail to know that the laws of war constitute a part

of the law of nations, and that those laws have been prescribed with tolerable

accuracy.

Congress

can declare war. When war is declared, it must be, under the Constitution . . .

.

. . The legitimate use of the great power of war, or rather the prohibitions

against the use of that power, increase or diminish as the necessity of the

case demands. When a city is besieged and hard pressed, the commander may exert

an authority over the non-combatants which he may not when no enemy is near.

All

wars against a domestic enemy or to repel invasions, are prosecuted to preserve

the Government . . . Because of the utter inability to keep the peace and

maintain order by the customary officers and agencies in time of peace, armies

are organized and put into the field . . .

[E]nemies

with which an army has to deal are of two classes:

1.

Open, active participants in hostilities, as soldiers who wear the uniform,

move under the flag, and hold the appropriate commission from their government.

Openly assuming to discharge the duties and meet the responsibilities and

dangers of soldiers, they are entitled to all belligerent rights, and should

receive all the courtesies due to soldiers. The true soldier is proud to

acknowledge and respect those rights, and every cheerfully extends those courtesies.

2.

Secret, but active participants, as spies, brigands, bushwackers, jayhawkers,

war rebels and assassins . . . When lawless wretches become so impudent and

powerful as to not be controlled and governed . . . armies are called out, and

the laws of war invoked. Wars never have been and never can be conducted upon

the principle that an army is but a posse comitatus of a civil magistrate.

The

Romans regarded ambassadors betwixt belligerents as persons to be treated with

consideration, and respect. Plutarch, in his Life of Caesar, tells us that the

barbarians in Gaul having sent some ambassadors to Caesar, he detained them,

charging fraudulent practices, and led his army to battle, obtaining a great

victory.

When

the Senate decreed festivals and sacrifices for the victory, Cato declared it

to be his opinion that Caesar ought to be given into the hands of the

barbarians, that so the guilt which this breach of faith might otherwise bring

upon the State might be expiated by transferring the curse on him who was the

occasion of it.

Under

the Constitution and laws of the United States, should a commander be guilty of

such a flagrant breach of law as Cato charged upon Caesar, he would not be

delivered to the enemy, but would be punished after a military trial . . .

.

. . The laws and usages of war contemplate that soldiers have a high sense of

personal honor. The true soldier is proud to feel and know that his enemy

possesses personal honor . . . Justice and fairness say that an open enemy to

whom dishonorable conduct is imputed, has a right to demand a trial . . .

It

is manifest . . . that military tribunals exist under and according to the laws

and usages of war, in the interest of justice and mercy. They are established

to save human life, and to prevent cruelty as far as possible . . .

Having

seen that there must be military tribunals to decide questions arising in time

of war betwixt belligerents who are open and active enemies, let us next see

whether the laws of war do not authorize such tribunals to determine the fate

of those who are active, but secret, participants in the hostilities . . .

Cicero

tells us in his offices, that by the Roman feudal law no person could lawfully

engage in battle with the public enemy without being regularly enrolled, and taking

the military oath. This was a regulation sanctioned both by policy and

religion. The horrors of war would indeed be greatly aggravated, if every

individual of the belligerent States were allowed to plunder and slay

indiscriminately the enemy's subjects, without being in any manner accountable

for his conduct . . .

.

. . These banditti that spring up in time of war are respecters of no law,

human or divine, of peace or of war, are hotes humani generis, and may be

hunted down like wolves . . . But they are occasionally made prisoners. Being

prisoners, what is to be done with them? If they are public enemies, assuming

and exercising the right to kill, and are not regularly authorized to do so,

they must be apprehended and dealt with by the military. No man can doubt the

right and duty of the military to make prisoners of them, and being public

enemies, it is the duty of the military to punish them for any infraction of

the laws of war. But the military can not ascertain whether they are guilty or

not without the aid of a military tribunal . . .

. . . But it may be insisted that though the

laws of war, being a part of the law of nations, constitute a part of the laws

of the land, that those laws must be regarded as modified so far, and whenever

they come in direct conflict with plain constitutional provisions[:]

"The trial of all crimes, except in

cases of impeachment, shall be by the jury; and such trial shall be held in the

State where the said crime shall have been committed; but when not committed within

any State, the trial shall be at such or places as the Congress may by law have

directed." (Art. III of the original Constitution, sec. 2.)

"No

person shall be held to answer for a capital or otherwise infamous crime unless

on a presentment or indictment of a grand jury, except in cases arising in the

land or naval forces, or in the militia when in actual service, in time of war

or public danger; nor shall any person be subject for the same offense to be

twice put in jeopardy of life or limb, nor shall be compelled, in any criminal

case, to be witness against himself, nor be deprived of life, liberty or

property, without due process of law; nor

shall private property be taken for public use without just compensation."

(Amendments to the Constitution, Art. V.)

"In

all criminal prosecutions, the accused shall enjoy the right of a speedy and

public trial by an impartial jury of the State and district wherein the crime shall

have been committed, which district shall have been previously ascertained by

law, and be informed of the nature and cause of the accusation; to be

confronted with the witnesses against him, to have compulsory process for

obtaining witnesses in his favor; and to have the assistance of counsel for his

defense." (Art. VI of the amendments to the Constitution.)

These

provisions of the Constitution are intended to fling around the life, liberty

and property of a citizen all the guarantees of a jury trial. These

constitutional guarantees can not be estimated too highly, or protected too

sacredly . . .

Nevertheless,

these exalted and sacred provisions of the Constitution must not be read alone

and by themselves, but must be read and taken in connexion with other

provisions [viz., regarding the law of nations and the laws of war] . . . to

act as a spy is an offense against the laws of war, and the punishment for

which in all ages has been death, and yet it is not a crime; to violate a flag

of truce is an offense against the laws of war, and yet not a crime of which a

civil court can take cognizance; to unite with banditti, jayhawkers, guerrillas

or any other unauthorized marauders is a high offense against the laws of war;

the offense is complete when the band is organized or joined. The atrocities

committed by such a band do not constitute the offense, but make the reasons,

and sufficient reasons they are, why such banditti are denounced by the laws of

war. Some of the offenses against the laws of war are crimes, and some not.

Because they are crimes they do not cease to be offenses against those laws;

nor because they are not crimes or misdemeanors do they fail to be offenses

against the laws of war. Murder is a crime, and the murderer, as such, must be

proceeded against in the form and manner prescribed in the Constitution; in

committing the murder an offense may also have been committed against the laws

of war; for that offense he must answer to the laws of war, and the tribunals

legalized by that law.

There

is, then, an apparent but no real conflict in the constitutional provisions.

Offenses against the law must be dealt with and punished under the

Constitution, as the laws of war, they being part of the law of nations; crimes

must be dealt with and punished as the Constitution and laws made in pursuance

thereof, may direct . . .

The

fact that the civil courts are open does not affect the right of the military

tribunal to hold as a prisoner and to try. The civil courts have no more right

to prevent the military, in time of war, from trying an offender against the

laws of war than they have a right to interfere with and prevent a battle . . .

My

conclusion, therefore, is, that if the persons who are charged with the

assassination of the President committed the deed as public enemies, as I

believe they did, and whether they did or not is a question to be decided by

the tribunal before which they are tried, they not only can, but ought to be

tried before a military tribunal. If the persons charged have offended against

the laws of war, it would be as palpably wrong of the military to hand them

over to the civil courts, as it would be wrong in a civil court to convict a

man of murder who had, in time of war, killed another in battle.

I

am, sir, most respectfully, your obedient servant,

JAMES SPEED.

Attorney General.

To the President

II

An

impromptu funeral service and viewing was held in the town of Michigan City,

Indiana during an 8:00 A.M. unscheduled stop of the Presidential Funeral Train.

The townspeople, who had previously scheduled a funeral in absentia, managed to use the 35-minute layover to best advantage

to honor their fallen leader.

Just

an hour after leaving Michigan City, the Lincoln Funeral Train reached Chicago.

Lincoln had been intimately connected

with Chicago for the bulk of his legal career and his political career. America’s Second City (and the first city of Illinois, which

had been Lincoln’s home since 1830), held a massive funeral for the man who had

been nominated as President there in 1860.

Rather than create chaos at the main

depot (which was and is the major rail hub for the entire Midwest) a special

receiving trestle was built out over Lake Michigan to hold the Funeral

Train.

The catafalque provided by Chicago was

a massive gothic construction that cost the city more than $15,000.00 (this did

not include the cost of the funeral service and procession). It flew a banner reading, THE HEAVENS ARE

DRAPED IN BLACK. So was the city, in

almost complete entirety.

Some 300,000 mourners (equal to the

entire population of Chicago at the time) participated in the event.

10,000 schoolchildren marched along

with their teachers. At least 5,000 soldiers marched in ordered ranks, followed

by city employees, business leaders, and a mass of ordinary and everyday human

beings. The city’s church bells rang, cannons were fired, and brass bands

played. The pall-bearers were Lincoln’s own friends.

While the procession was not as lengthy

as the ones in New York and Washington, reviewing stands along the route

groaned under the weight of observers. Many people climbed trees for a better

view. Several toppled from the weight of climbers.

President Lincoln’s body was laid in

state in the Old Cook County Courthouse; he remained there for 27 hours. Some

250,000 mourners viewed the body --- again, nearly equal to the entire

population of Chicago.

For the first time since the

assassination, news editors and commentators began to publicly criticize the

seemingly endless cycle of funerary rituals. By the First of May the preserved

corpse was being described as having “sunken, shrunken features.” Viewers noted

that Lincoln’s face was progressively “growing . . . darker” (it would

eventually turn an iconic bronze due to his wounds).

Particularly in the South, editors

blamed Northern “morbid curiosity” for the President’s still being above

ground, by way of an acceptable mocking of the Yankees.

Northern editors accused Edwin Stanton

of “desecrating [Lincoln’s] remains” by “making a show of all that was mortal

of a fellow-man.”

But many Americans, belatedly, realized

that with the loss of Lincoln --- a truly remarkable man --- that the course of

human events had been altered irrevocably, and they grasped at what little they

understood of him by way of honoring him.

III

The first Memorial Day celebration was

held in Charleston, South Carolina by former slaves. The newly freed chose to

honor 257 dead Union soldiers who had been hastily buried in a mass grave on

the grounds of a former Confederate prison camp. The Freedmen dug up the bodies

beginning on April 16th. They worked for two weeks nonstop in order to give the

dead a proper burial as a mark of gratitude for their role in the fight for

freedom. On this day, the African-American community of Charleston held a

parade in which 10,000 people participated, including 2,800 children. Flowers

were laid on the new graves in accordance with the new custom being observed in

connection with President Lincoln’s funeral services.