“I cannot

feel myself a beaten man” --- Jefferson Davis

I

It

is a private meeting between the two men, for Grant came to deliver a

tongue-lashing to his friend and subordinate. Given that “Grant stood by

Sherman when he was crazy and Sherman stood by Grant when he was drunk” the

exchange between the two men was probably relatively mild. Still, Grant had to

deliver the bad news that Sherman’s peace terms as set forth in his

“Memorandum, or Basis of Agreement” of April 18th were thoroughly

unacceptable to the Johnson Cabinet.

Sherman

no doubt wondered out loud whether the U.S. Government really wanted peace.

Grant

surely answered undoubtedly, but then

reminded Sherman that the reasonable and compassionate voice of Abraham Lincoln

had been stilled.

The

two men condoled one another for certain, but then Grant explained the tenor

and tone of the Cabinet meeting of the 21st. Sherman grasped

immediately how close he had come to ruin --- even death. Grant grimly reminded him that this was not

the same Administration that had set forth terms at City Point. It was a far

angrier Government, bent on retribution, hoping the Confederacy would fight,

hoping it would draw the last life’s-blood from the South.

And

then Grant mentioned the memorandum of March 3rd, the Memorandum

that limited battlefield generals to accepting only battlefield surrenders.

Sherman

possibly looked puzzled when Grant produced President Lincoln’s memo.

If I had known about

this, he

said, I would never have negotiated those

terms.

A

little acidly, Sherman added that he could not understand why every barkeep in

the District of Columbia seemed to know more Military Intelligence than the

Generals in the field.

Grant

was taken aback. He realized that Sherman had been left out of the loop ---

inadvertently --- and that the same problem might reoccur.

You must offer Johnston

the selfsame terms that I granted Lee at Appomattox. No more. No less. That is

what the Cabinet and the President all want. Just that.

Good

friend that he was to Sherman, Grant fell on his sword upon his return to

Washington, explaining that Sherman had negotiated with Johnston in good faith

but with incomplete information. He took the blame for not forwarding President

Lincoln’s March memorandum. Nobody really wanted to lambaste the Hero of

Appomattox, so the matter was dropped. And Grant forwarded Lincoln’s terms ---

the Appomattox terms --- to all his subcommanders. When the Civil War finally

ended, everyone would have the same expectations.

Sherman

was left with a conundrum. If Johnston did not accept the terms given to Lee,

the war was set to resume on April 26th. And Sherman had no doubt it would.

II

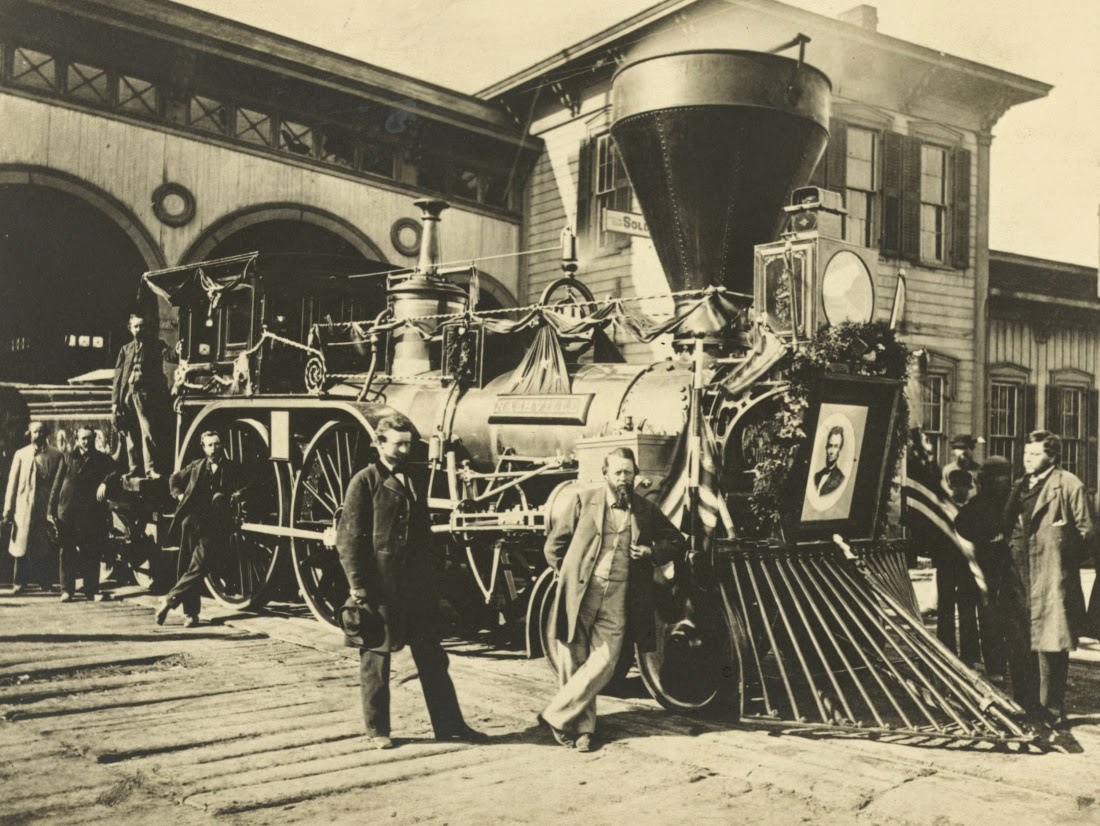

Abraham

Lincoln’s body left Philadelphia at 4:00 A.M., and reached Trenton, New Jersey

at 6:00 A.M. for only a thirty minute stop. Crowds thronged the railroad

station, hoping to get a glimpse of the fallen President in his coffin. Oddly

enough, Trenton was the only State capital where Lincoln’s body did not lie in

state --- in fact it was not even removed from the train, and people had to

content themselves with gazing at the President through the windows of the

hearse car.

At

10:50 A.M. the Funeral Train reached Jersey City. Lincoln’s body (and Willie’s

body) was ferried across the Hudson to New York City (there were no Hudson

River crossings as there are today).

Once

on the New York shore, a vast procession accompanied the President’s body to

City Hall. The building was draped with

a huge banner reading THE NATION MOURNS.

At

1:00 P.M. the President’s body was placed in City Hall for viewing. At least

500,000 mourners passed by the casket.

New

York’s leadership made an error in judgement. The President had never been

especially popular in New York, with its Copperhead tendencies, and so they

expected a relatively small turnout. To view the body, mourners were required

to climb a set of stairs in City Hall, pass the coffin, and descend. This

caused an unprecedented bottleneck, since only two lines of mourners could pass

by at a time, and no one could linger. For every person that passed the casket,

two never made it inside the building.

It

was in New York that the only photographs were taken of Lincoln lying in state.

Edwin Stanton was outraged by what he called “ghoulishness,” and Federal agents

seized the glass negatives and smashed them. Only one, kept by Stanton as a

keepsake, was known to have survived and it was published finally in 1952.

III

After

spending the night at the Lucas cabin, John Wilkes Booth and David Herold forced

Charlie Lucas, the son of the owner of the cabin, to drive them south at

gunpoint. At the town of Port Conway,

they asked to be ferried across the Rappahannock River. The ferryman, William

Rollins agreed to take them across, but not until he set his fish traps. While they waited, several Confederate

soldiers released from Mosby’s Rangers arrived at the ferry landing. Herold

engaged them in conversation.

Upon

discovering that the men were from Mosby’s command, Herold asked them if they ever

knew Lewis Powell (who was a former Ranger). Believing he was safe territory,

he bragged to the three Confederate soldiers that Booth was the assassin of

President Lincoln. Ultimately, this admission, made in the hearing of the

ferryman, proved to be his and Booth’s undoing.

After

crossing the river, William Jett, one of the Rangers escorted Booth and Herold

to the Peyton family house in Port Royal, Virginia, but the spinster sisters

who lived there refused to give Booth and Herold shelter, insisting that it would

be unseemly to have two single men alone with them in the house. A frustrated Jett, at this point no doubt sorry

he has involved himself with the two fugitives, led them to the Garrett farm

near the crossroads of Bowling Green. A drained Booth, using the name of “Boyd,”

rested at the Garrett farm while Herold and the Confederates traveled into Port

Royal to get drunk. Later, much too intoxicated to return to the Garrett farm,

Herold spent the night away from Booth, in Port Royal.

On

this same day, the 16th New York Cavalry is dispatched into southern

Maryland to find John Wilkes Booth.

IV

Jefferson

Davis writes to his wife Varina in Abbeville, South Carolina, advising her to

move further south. He also tells her of Lincoln’s death. Varina later wrote:

“I burst into tears of

sorrow . . . for the family of Mr. Lincoln and a thorough realization of the

inevitable results for the Confederates.”

Varina

is also convinced that the death of Lincoln will put a price on Davis’ head.

While

Davis is writing to Varina he receives a copy of Sherman’s “Memorandum, or

Basis of Agreement” from Johnston. Looking it over, he shakes his head, telling

John C. Breckinridge that not even Lincoln would agree to such terms. He is

certain that Johnson and Stanton will reject them out of hand.

Nevertheless,

the gathered Confederate Cabinet urges Davis to sign off on the terms. Davis

balks --- his signature will mean surrender. “I cannot feel myself a

beaten man,” he tells his fellow Confederates. Davis’ back is stiffened by General Wade

Hampton C.S.A. who is present, and swearing a blue streak that he, for one,

will never surrender to the Yankees.

Hampton reminds Davis that 40,000 unfought troops still remain in the

Trans-Mississippi. (In fact, Hampton has no real clue what is happening in that

Military Department).

“We

cannot reasonably hope for the achievement of independence,” retorts John H.

Reagan, the Confederate Postmaster-General. Other voices agree.

Davis

finally signs off on the Memorandum, deciding that the war will go on if

Johnson and Stanton in the North reject Sherman’s terms. He tells his Cabinet

that rejection of the terms is a certainty.

A

bare hour after Johnston receives Davis’ signed copy, a messenger from Sherman

advises him the deal is off. The

cease-fire clock begins to tick. On the afternoon of the 26th, 48

hours from now, the killing will begin again.